âFor the longest time, we were told Article 370 cannot be abrogated notwithstanding political rhetoric. But eventually, itâs gone. The Supreme Court has also upheld the decision. Similarly, what is the guarantee that CAA [Citizenship (Amendment) Act], or NRC [National Register of Citizens] or Uniform Civil Code will also not be implemented â considering that the ruling party has the numbers?â asked a student.

A response to this came from the departmentâs professor Arshi Khan.Â

âLook, it may have been done, but I donât accept it. Article 370 could not have been scrapped as it formed a basic structure of the Constitution. A lot of things can be done using law as an instrument, but as long as we donât accept it, it doesnât matter. The same would hold true for the laws you referred to,â he said.Â

Khanâs answer left many students to wonder if he would adopt a similar stance on another debate playing out not just on the campus, but in the nationâs highest court.

It is the question of whether AMU is a minority institution under Article 30(1) of the Constitution of India that grants minorities the right to establish and administer educational institutions.Â

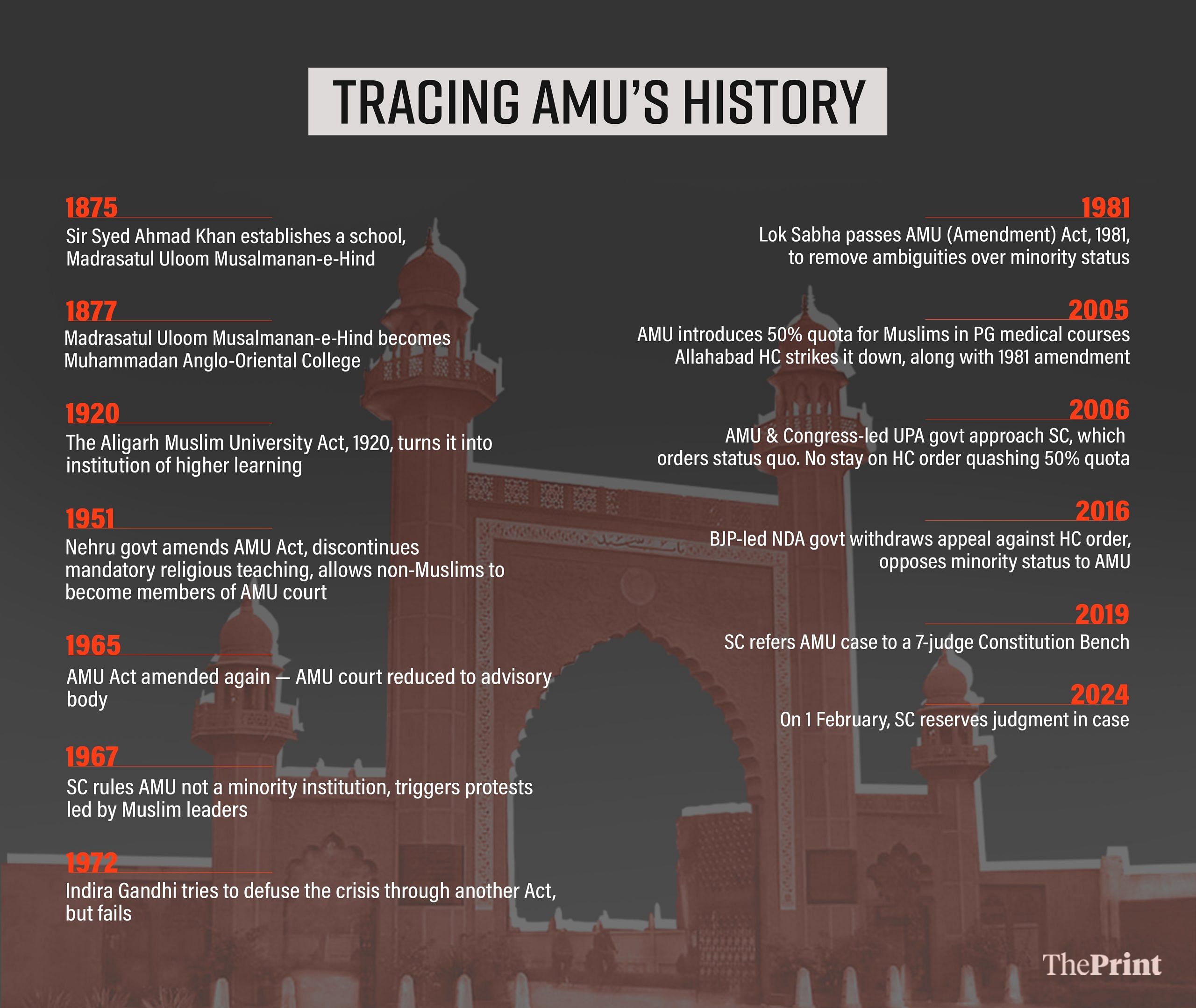

On 1 February, a seven-judge Constitution bench of the SC reserved the judgment on the issue after hearing both sides for eight days.Â

Also Read: AMU asked for certificates proving students are Ashraaf till 1947. Nothing has changed

History of the case

Established in 1877 as Mohammedan Anglo-Oriental (MAO) college by Muslim reformer Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, AMU was incorporated through the Aligarh Muslim University Act, 1920.Â

Since then, the original Act has seen a series of amendments, beginning in 1951, when the Jawaharlal Nehru government allowed even non-Muslims to be members of the institutionâs court â its highest governing body â and discontinued mandatory religious instruction.

In 1965, the internal reservation for AMU students was reduced to 50 percent from 75 percent, while another amendment was also brought in, further curtailing the powers of the court â reducing it to an advisory body.Â

Two years later, the Supreme Court upheld the amendments, saying AMU was incorporated by an Act of the central legislature, in the S. Azeez Basha vs Union of India case.

âIncidentally, the AMU was not even a party to the case giving it no chance to defend itself,â said Obaid Ahmad Siddique, AMU teachersâ association (AMUTA) secretary.

As the shadow deepened over the minority character of the institute, a wave of protests, on and off the sprawling campus, broke out, featuring many student leaders, including now Kerala Governor Arif Mohammed Khan who served as the AMU studentsâ union president in 1972-73, said Mohibul Haque, AMU political science department professor.

Under fire, the Indira Gandhi government tried to assuage the fears of the Muslim community, saying fresh legislation would be brought to restore the basic character of the university, according to the book Education and Politics: From Sir Syed to the Present Day: the Aligarh School, authored by Shan Muhammad.Â

Indira told the Muslim delegation that she would take steps to retain the âspecial characterâ of the university, avoiding using the phrase minority character, which allowed the apprehensions of the Muslims to fester, the book added.

In 1981, the Lok Sabha passed the Aligarh Muslim University (Amendment) Act, 1981, brought by Indira Gandhi after returning to power, which amended the original Act to specify that âUniversityâ means âthe educational institution of their choice established by the Muslims of India, which originated as the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College, Aligarh, and which was subsequently incorporated as the Aligarh Muslim University.â

It left the composition of the court unchanged, though leading Chief Justice of India D.Y. Chandrachud, who is also on the seven-judge Constitution bench that heard the AMU case, to observe during the 1 February hearing that the 1981 amendment was a âhalf-hearted jobâ. âThey made a few concessions but they never took it back to 1920, it could be reflected upon,â the CJI said.Â

During the hearing, Chandrachud also questioned the Centre’s contention that it does not accept the 1981 amendment.

“Parliament is an eternal, indestructible body under the Indian Union, and irrespective of which government represents the cause of the Union of India, Parliament’s cause is eternal, indivisible and indestructible and we can’t hear the Government of India say that amendment, which the Parliament made, is something I don’t stand by. You have to stand by it,” the CJI observed.

Speaking to ThePrint at his Aligarh residence, historian Irfan Habib, a professor emeritus at AMU, said he was among those who firmly opposed the 1981 amendment then.Â

Writing in Peopleâs Democracy, the mouthpiece of the CPI(M), Habib had severely criticised the move, saying it was âdesigned to placate Muslim politicians who wished to control the university through the university court.â

Habib, now 92, said his position then was dictated by the context of the times.Â

âThe fear then was about communal Muslim domination. Now itâs the other way round,â he said, adding that he was in favour of the existing arrangement where AMU offers no caste or religion-based quota in admissions.

The 1981 amendment was struck down by the Allahabad High Court in 2005 after a clutch of petitioners had approached it against the AMU’s decision â approved by the then United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government â to reserve 50 percent seats for Muslims in the post-graduate medical degree courses under the university.Â

In 2006, however, the Supreme Court took up the matter, directing the status quo to be maintained on the minority character of the university, while granting no stay on the Allahabad HC quashing the 50 percent quota for Muslims in medical PG courses.

The UPA government, along with the AMU, also challenged the Allahabad HC decision before the Supreme Court. However, in 2016, by which time the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was in power, the central government withdrew its appeal â choosing to oppose the AMUâs minority status.Â

âRemember, when I had opposed the 1981 Act, there was no quota in higher education. But, now, if the Centre has its way in the Supreme Court, it will force AMU to implement reservations for SC, ST and OBCs. I have never supported a quota for Muslims in AMU. But implementing SC, ST and OBC reservations means there will effectively be a quota for Hindus in AMU. Must government institutes have no freedom to fix their own admission policies?â Habib asked.

Also Read: This Indian watchdog is cleaning up âmessâ in academiaâfalsification, fabrication & fraudÂ

AMUâs minority character

Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath has, in the past, often questioned the non-implementation of the reservation policy in AMU.Â

âEk prashna yeh bhi pucha jana chahiye jo keh rahe hain ki Dalit ka apmaan ho raha hai⦠ki akhir Dalit bhaiyon ko Aligarh Muslim University aur Jamia Millia University mein bhi arakshan dene ka labh milna chahiye, is baat ko uthane ka karya kab karenge. (One question that should also be asked is by those who say that Dalits are being insulted⦠when will the work of raising the issue that Dalit brothers should also get the benefit of reservation in Aligarh Muslim University and Jamia Millia University, be undertaken?â he said in June 2018.

The Central Educational Institutions (Reservation in Teachers Cadre) Act, 2019, mandates reservation in all higher educational institutions, except institutions of national and strategic importance and minority educational institutions.Â

The immediate fallout of AMU losing the case in the SC would be the need to follow the reservation policy, which, many students and teachers feel, may lead to a decline in the number of Muslim students in the university that currently has a provision for up to 50 percent internal quota for students regardless of religion or caste.Â

âThat’s because the beneficiaries of the internal quota system are mostly Muslim students who study in the schools or colleges affiliated with AMU. It helps the university maintain its minority character. Itâs also true that most postgraduate professional courses also have a good number of non-Muslims. In medicine it is nearly 40 percent,” said Siddique.

Professor Aftab Alam of AMUâs department of strategic and security studies told ThePrint that stripping AMU of its minority status will also put a question mark on the status of all minority educational institutions in India. âAll minority institutions established by state legislations will also lose their minority status going by the Centreâs argument.”Â

Senior advocate Rajeev Dhavan, who represented AMU in the SC, also made this point in the court, pointing out that if every minority institution, which sought recognition under a statute to have their degrees considered valid, is thought to have automatically given up their minority status, then Article 30(1) would be rendered ineffective.

Professor Shafey Kidwai, who is the director of AMUâs Sir Syed Academy, said the AMU had no option but to get incorporated under a central legislation in 1920 to ensure that its degrees are considered valid.Â

âThe Centre cited the case of Jamia Millia Islamia, which had not approached the British administration to get incorporated. But the fact is that Jamia Millia Islamia did get instituted under an Act of Parliament after independence,â Kidwai said.

Jamia Millia Islamiaâs status as a minority institution has also been challenged by the Modi government in the Delhi High Court. In an affidavit filed in 2018, the central government contested the 2011 order of the National Commission for Minority Educational Institutions (NCMEI) recognising Jamia as a religious minority institution on the grounds that it is a university set up under central legislation.

âArticle 30 is the only safeguard specifically for minorities. There is a misconception that it accords some kind of privilege to minorities. But as Justice Hans Raj Khanna underlined in the Ahmedabad St Xaviers College vs State of Gujarat case, part of the principle of the right of equality is the fact that unequal cannot be treated equally. He had also reminded that attempts to play with Article 30 would amount to an act of breach of faith,â said Professor Alam.

Professor Haque echoed Alam, saying the AMU case will also determine if Article 30 faces any dilution.

âArticle 30, unlike Article 19 (freedom of speech and expression), does not come with any reasonable restrictions. Institutions such as AMU can also be considered as autonomous minority spaces,â Haque said.

Many also feel that no matter on whose side the court rules, the dilution of AMUâs minority character has been underway for some time.

Vacant seats and positionsÂ

While in judicial forums, the institute fights to preserve the autonomy of its court, AMUâs highest decision-making body, which also shortlists names of candidates for its vice-chancellors, as many as 81 of the 194 positions in the forum remain vacant.

The vacant positions include that of the vice-chancellor, as AMU is currently being run by an acting VC since April 2023 when Tariq Mansoor stepped down from the post. Post-resignation, Mansoor was appointed as a vice-president of the BJP and also received a nomination to the Uttar Pradesh legislative council by the party.

âThere are no student representatives in the court as no student body elections have been held since 2018. It is filled with people who are nominated faces and are expected to sign on the dotted line,â said Siddique of AMUTA. Â

He added: âLike the post of V-C, many heads and principals of colleges under AMU are being run by ad hoc faces. It will be more apt to call AMU âAd Hoc Muslim University nowâ.âÂ

According to official records, apart from student representatives, the vacant positions include representatives of faculty, non-teaching staff, industry experts, and Muslim cultural exponents, among others.

AMU operated without a full-time V-C for such a long duration only once in the past â between October 1989 and October 1990.Â

While the decision to appoint a full-time V-C remains pending with the Visitor â the President of India â the process through which three names were picked drew allegations of âconflict of interestâ.Â

The current acting vice-chancellor, Mohammed Gulrez, chaired the meeting of the executive council on 30 October 2023 and also voted for his wife Naima Khatoon, principal of AMUâs womenâs college, who was among those in contention.

Professor Murad Khan, a member of the executive council who teaches at AMUâs department of foreign languages, was among those who submitted dissent notes against the presence of Gulrez at the meeting.

âHad he not voted, she would have received five votes in her name and would not have been picked after the first round of voting. It was a clear case of conflict of interest. He (Gulrez) should not even have been there. His mere presence may have influenced the choices of those in the body who were nominated by him,â Khan said.Â

The entire process was later challenged in the Allahabad High Court, which will now hear the matter next month.

ThePrint reached Gulrez for his comments through appointment requests, emails and texts. This report will be updated if a response is received.

âThe AMU Act Section 19 Clause 3 empowers the V-C to make decisions that are to be taken immediately without always going to the executive council. The VC can act and later get such decisions ratified by the council, which can even modify or cancel them. But it ensures that nothing comes to a standstill. An acting V-C cannot do that,â explained Hamza Sufiyan, a former vice-president of the AMU studentsâ union.

AMUTAâs Siddique said many financial decisions are stuck, leading to a situation where funds worth almost Rs 7.5 crore, which came as grants, may lapse as many projects await sanction. Â

Meanwhile, even as AMU anxiously awaits the verdict of the apex court, a sense of foreboding also hangs heavy on the campus, which witnessed violence in 2019 during student protests against the CAA as police entered the campus and later drew charges of assaulting students.Â

âThe thing is, nearly 50 percent of AMU students stay on the residential campus. So it cannot afford to have a repeat of 2019. But, there is widespread apprehension that the loss of minority status may trigger protests. After all, there is a precedent of that happening after the 1967 SC judgment. Whichever way the court rules, I hope better sense prevails among the students,â said a senior faculty member at the institute.  Â

(Edited by Richa Mishra)

Also Read: Nine-year-old Ashoka University is asking the most important question. Who am I?

Â